No audio available for this content.

Notre Dame de Paris, the French capital’s cathedral, has reopened its doors five years after a devastating fire, showcasing its restored interior after extensive rebuilding work. The restoration, costing approximately €700 million ($737 million), was financed entirely by donations from around the world.

On April 15, 2019, Notre Dame tragically went up in flames, with the spire collapsing and the roof being destroyed. The following years were dedicated to rebuilding the cathedral, including the reconstruction of the spire and the restoration of stained glass and woodwork.

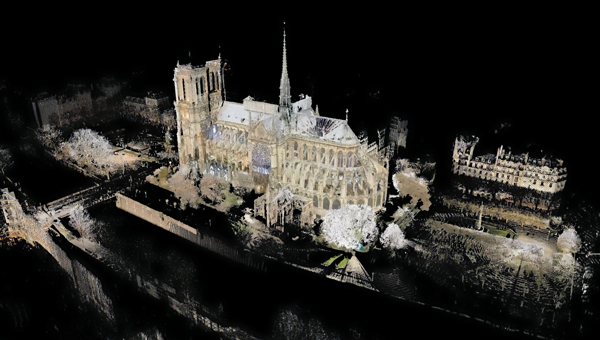

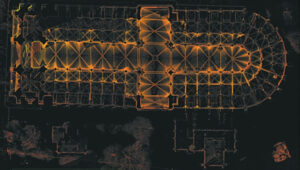

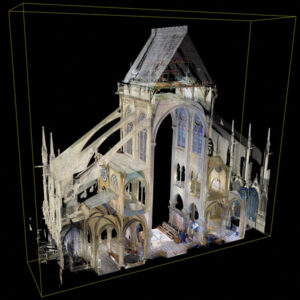

A crucial element in the restoration process was the point cloud data collected by Professor Andrew Tallon, an architectural historian from Vassar College, in 2010. Tallon’s project, which aimed to fully understand the Gothic structure and identify structural anomalies, involved creating a precise 3D model of Notre Dame using a Leica Geosystems terrestrial laser scanner.

This cloud of 1 billion points — with a TruView released by Leica Geosystems available to view here — proved to be indispensable for the digital recreation of the cathedral’s interior and exterior. Tallon’s laser scans were the only truly accurate as-built measurements of Notre Dame, translating point clouds into detailed representations of its buttresses, ribbed vaults, stained glass, ornate carvings and other architectural details.

Tallon, who died of cancer in November 2018, pioneered the use of laser technology to create a digital model of Notre Dame. Members of the restoration team and architectural historian Lindsay S. Cook — assistant teaching professor of architectural history at Pennsylvania State University, and a protégé of Tallon’s — said his work was critical to the cathedral’s rebuilding and refurbishing.

The value of point cloud data

While modern restoration efforts cannot fully replicate the artistry of centuries past, Tallon’s scans have been instrumental in reconstructing the Gothic cathedral, allowing architects to come remarkably close. Tallon’s groundbreaking work remained a vital resource for restoring the iconic cathedral to this day.

His meticulous 3D scans of Notre Dame provided architects with information crucial for the cathedral’s reconstruction, including:

Precise 3D models: Tallon’s precise 3D model of Notre Dame included intricate details of the cathedral’s architecture, such as flying buttresses, rib vaults, stained glass windows and ornate carvings. This level of detail was unmatched by any historical drawings or records, which often lacked precision.

Dimensional and formal reconstruction: Pascal Prunet, one of the architects tasked with rebuilding the cathedral, said in an interview with Lindsay S. Cook that the point cloud data provided an “exact trace” of the cathedral’s state at the time of scanning, allowing him and his team to reconstruct elements — such as the vaults — “without hesitation” regarding dimensions or forms. This was essential for accurately rebuilding complex structures such as flying buttresses and rib vaults.

Structural analysis: The scans revealed structural details that were previously unknown, aiding in understanding how the cathedral was originally constructed and how it changed over time. This information was vital for designing custom supports and ensuring structural stability during reconstruction.

Integration with modern technology: The point cloud data was integrated into Building Information Modeling (BIM) processes, which allowed architects to create a digital twin of Notre Dame.

Restoration guidance: The scans provided a highly detailed record of Notre Dame’s pre-fire condition, which helped restoration professionals select appropriate techniques for stabilizing and rebuilding various parts of the cathedral.

Why precision matters

On Oct. 25, 2023, Philippe Villeneuve, architect in chief of historical monuments in charge of Notre Dame, and Pascal Prunet, a fellow restoration architect, delivered a Claflin Lecture at Vassar College in New York. They discussed their efforts to shore up, conserve and restore the cathedral since the devastating fire.

The two architects highlighted the crucial role Tallon’s laser scan of the cathedral played in their restoration process. They shared how this detailed digital model provided them with precise measurements and structural information, enabling Notre Dame to, in essence, “guide its own restoration.” By relying on this accurate data, the team could ensure its work remained faithful to the iconic cathedral’s original design and construction.

When speaking with Cook, Prunet shared, “At Notre Dame, we are doing an enormous amount of work, but we are not doing creative work; we are putting things back together again.” Villeneuve added, “What we’re doing isn’t very personal.” Tallon’s laser scan has enabled the architects to allow Notre Dame to “speak for itself,” according to Villeneuve.

Tallon had sent a copy of his point cloud to Villeneuve’s predecessor, Benjamin Mouton, before Mouton retired in 2013. After the 2019 fire, Marie Tallon saw that the architects had access to her late husband’s work. During their 2023 lecture and in a follow-up interview, Villeneuve and Prunet said Tallon’s scan — which Prunet called an “exact trace” of the state of the building at the time it was scanned — had been used in numerous ways since the fire.

For example, it aided the design of the wooden centering custom-made to cradle each unique flying buttress and rib vault and to rebuild the damaged vaults and the sole transverse arch destroyed when the tip of the spire separated from its base and fell westward, becoming a projectile that crashed into the nave.

“Andrew Tallon’s point cloud, well, it’s a bit like listening to a Mahler symphony,” said Prunet, alluding to the scan’s scale and complexity. Prunet continued, “It’s a recording,” but one that “needs to be decrypted.”

Tallon’s laser scan of Notre Dame has proven invaluable in the restoration process. This digital twin, created in 2015, offers unparalleled precision and detail, capturing the cathedral’s every nuance with accuracy up to 5 mm. This level of detail allowed the restoration team to address the structure’s complexities and make informed decisions about the rebuilding process, ultimately helping to preserve Notre Dame’s authenticity and historical integrity.