No audio available for this content.

It happened in the blink of an eye. Less than a blink. Far less, actually. Slightly more than one one-thousandth of an eye blink, according to calculations. In that amount of time, one of your eyelashes traverses 10 micrometers on its journey toward your lower eyelid.

And yet it was long enough to throw computers and communications systems around the world out of whack, generate thousands of alarms, and pull engineers from their beds at 2 a.m.

One occurrence might have been enough to do all that. I’m not sure. But it kept happening over and over again. Thus the alarms, the out-of-whackness, the sleep deprivation. At least it did not generate massive financial trading sell-offs, blow holes in national security, or shut down Facebook, Instagram and Snapchat. For that, we may be thankful.

But it might have.

“On 26 January at 12:49 a.m. MST, the 2nd Space Operations Squadron at the 50th Space Wing, Schriever Air Force Base, Colo., verified users were experiencing GPS timing issues. Further investigation revealed an issue in the Global Positioning System ground software which only affected the time on legacy L-band signals. This change occurred when the oldest vehicle, SVN 23, was removed from the constellation. While the core navigation systems were working normally, the coordinated universal time timing signal was off by 13 microseconds which exceeded the design specifications. The issue was resolved at 6:10 a.m. MST, however global users may have experienced GPS timing issues for several hours.” (This excerpt from an U.S. Air Force communiqué appears in a brief news account.)

“The Joint Space Operations Center at Vandenberg AFB has not received any reports of issues with GPS-aided munitions, and has determined that the timing error is not attributable to any type of outside interference such as jamming or spoofing. Operator procedures were modified to preclude a repeat of this issue until the ground system software is corrected.”

Companies and their time-servers around the world were subsequently hit by up to 12 hours of system warnings after 15 GPS satellites broadcast the wrong time, according to Chronos, a UK-based time-monitoring firm.

Telecommunications companies constitute only a small part of industry users who rely on the highly precise accuracy of time measurements — supplied by GPS — to control data flow through their networks. Global financial networks and trading markets similarly depend on GPS, as do electrical power grids and many other sectors of critical national infrastructure. These companies and networks invest significantly in highly sophisticated equipment to monitor said timing accuracy as conveyed by GPS signals. Because billions, make that trillions — or actually even more — are riding on it.

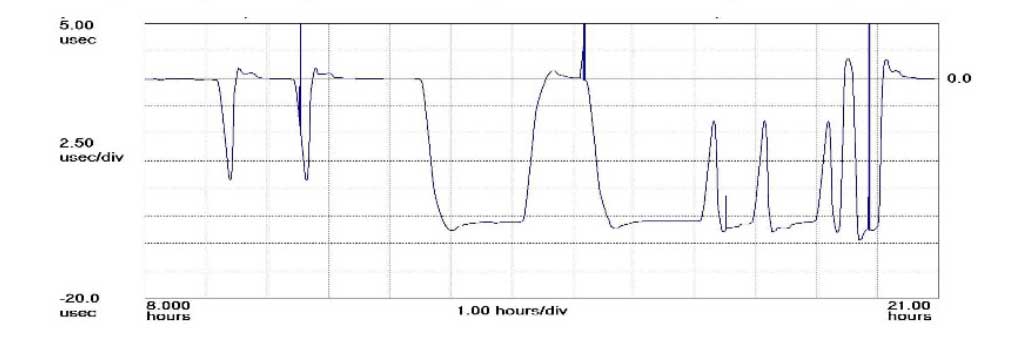

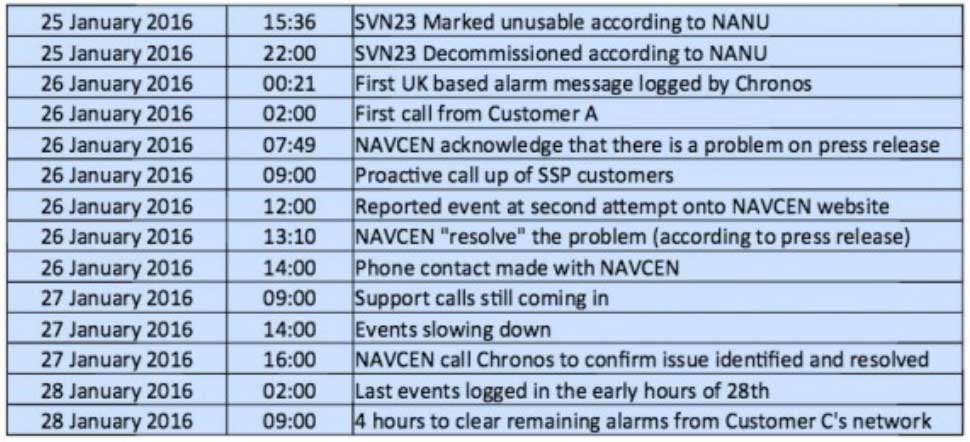

A week after the eye blinks, Chronos Technology released a white paper describing the ensuing fallout for its clients, who are timing equipment users in more than 50 countries around the world. Table 1 from the white paper reports the experience of a few during the event. One company registered nearly 2,500 alarms from its timing equipment during the outage.

At one point during the crisis, according to the white paper, “it appeared that the GPS error had cleared and the Chronos SSP Manager was able to force the units out of holdover. However the scale of the problem escalated as these sites went back into holdover along with dozens of other sites suffering GPS-based timing issues. It was apparent at this point that there was something amiss with the GPS constellation itself.”

Later on, the report states, “This event linked to SVN23 has been one of the most significant service affecting issues for GPS timing users and sits alongside the April 1st 2014 GLONASS outage in scale — however its impact on global timing services is much more extreme.”

Ominously, “Chronos is aware of other more catastrophic impacts to networks and non-telecom applications which were not under supply and support contracts.”

As Loran Is Our Savior. At least one timing-reliant company was not disturbed by the problems, because it was testing an alternative timing service provided by enhanced Loran (eLoran) signals.

Unfortunately for them — and for the rest of us — eLoran has a very uncertain future. In fact, they were lucky to have an eLoran signal at all on January 26, because it was supposed to have been turned off on December 31. Somebody must have forgotten to tell the operators at the Anthorn giant antenna field in Cumbria to go home.

France, Norway, and the United Kingdom, three countries that had been keeping eLoran alive, officially abandoned the effort at the end of last year, reportedly because of lack of leadership from the United States.

The U.S. government decommissioned all its Loran stations a few years ago, even going to the extent of blowing some of them up (perhaps to prevent them from falling into the hands of subversives). Despite a recent reinvigorated interest in enhanced Loran technology, it may be too little, too late.

Whoa, Nellie. The first recorded use of the term “back-up technology” occurred in 1892, when farmers were urged not to prematurely abandon their mules in favor of John Froehlich’s new gasoline tractor.

That admonition, however prudent, has since passed from view. But the concept remains sound. It has surfaced many, many times in GPS World magazine. Certainly not the first incidence, but the farthest back that I can retrieve via search on our website, came in 2007 from Defense contributing editor Don Jewell. “Why do we need a backup? Here is a classic case in point.” He describes a Joint Navigation Conference briefing on a surprise jamming incident that had occurred in January of that year.

In 2009, we reported on an Independent Assessment Team (IAT) report that “unanimously recommends that the U.S. government complete the eLoran upgrade and commit to eLoran as the national backup to GPS for 20 years.” The report was written in 2007, but quashed by the Department of Transportation and Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Executive Committees that commissioned it. Its public release came only after an extensive Freedom Of Information Act (FOIA) battle.

The U.S. government proceeded, despite its paid experts’ recommendations, to blow up those old Loran stations. The current renewed interest and the Wildwood experiment are worthy — more than worthy. Can they prevail? Can they survive blind reliance on a single string of vulnerable technology?

Indubitably, the critical role of GPS back-up was advanced prior to 2007, I just can’t document it this morning by deadline. For the sake of argument, let’s take April 12, 2007, as our start.

We are now 3,229 days out. That’s 77,496 hours, or nearly 279 million seconds. Correct me if wrong, but that appears to make 21.5 million-million times the length of January’s GPS timing error. Surely sufficient to blink a few times, scratch one’s head, and wonder.

Could there be a better way?

Paul McBurney

Hi Alan,

Nice article. I like the strip chart that shows a timing jump of a few micro seconds over a number of hours. After reading, I am not sure about the exact reason. Would this imply that the error was in the navData, rather than the timing of the C/A data? This would explain why the problem persisted. More specifically, was it in an ephemeris or almanac? The later would be more like to cause an error longer than the normal applicability of the ephemeris which is usually 2 hours these days. It think it is always interesting to see how the various receiver manufactures pontificate on their “superiority” in how their integrity checks caught the problem. But the good news is that these real life test cases become part of the new regression test cases. Many interesting questions come to mind..wow as SBAS affected, civil aviation, the DRONES??? A great forum would be to reach out to GNSS receiver manufactures to aggregate integrity logic, or cross checking, that we can all integrate into our next SW build to improve reliability. Thanks for chance to chime in.

Cheers

Paul

Martin Burnicki

At Meinberg we were able to do some debugging, I’ve posted the results here:

https://www.febo.com/pipermail/time-nuts/2016-January/095692.html

and here:

https://www.febo.com/pipermail/time-nuts/2016-January/095714.html

Martin

Brian Inglis

It appears that the problem was actually caused by an operator at ground control entering incorrect timing parameters for transmission to the SVs.

A parameter which is normally very close to zero was entered as 13.6us, causing a 13.6us error in time solutions when converted to UTC. This was confirmed by receiver manufacturers who had captured the transmitted GPS frames and found the incorrect parameter being transmitted.

See:

https://www.febo.com/pipermail/time-nuts/2016-January/095692.html

https://www.febo.com/pipermail/time-nuts/2016-January/095714.html

https://www.febo.com/pipermail/time-nuts/2016-January/095756.html

Paul McBurney

Wow. Hand input of timing parameters, how is it that there are still humans in the loop???. But its still seems this was a navData error, not change in the spacecraft CA epoch timing. In either case, this would imply the error appears in the linearized psuedoranges when applying the satellite clock corrections. I would think that most receivers would be able to easily reject this SV in the linearized pseudorange innovations check. After all, with so many SVs, a single timing error is the original error mode that RAIM and TRAIM were designed to detect and eliminate. Also, I would expect SBAS would have quickly seen the same error. I would think that it would only impact receivers operating on few SVs, such as 2-3 where RAIM has observability issues. For a static timing receiver, this is a bread and butter failure mode and outputting bad time for this reason would be a real embarrassment. I have written code to catch this case myself: I would really enjoy knowing how it performed. By the way, this article is slanted towards timing, but it is likely that receivers with poor RAIM geometry would also experience position errors on the order of the 13micro seconds, where each microsecond is about 300m. So at least km level position errors if RAIM failed. Would love to hear how SBAS receivers performed that were using the messasge as a DGPS feed. Thanks, Paul

Martin Burnicki

In this case the GPS timing was not affected as far as we could see.

All the pseudo-range stuff, satellite clock correction etc. was fully consistent, so there was no problem for a receiver to determine the GPS time or its own position correctly, and thus navigation wasn’t affected either.

Only the UTC correction parameter transmitted in the navigational message was wrong, so only when receivers converted the determined GPS time to UTC by adding the wrong the UTC offset parameter the result was wrong by a few microseconds.

Paul McBurney

Hi Martin, thanks for the very helpful description. So in terms of trying to make a RAIM algorithm to detect the problem, is there any redundancy on this parameter to allow a cross check? For example, was the UTC correction parameter seen in the almanac of all satellites, or was there a period where some had good and some had bad offset? My guess is that the correction would have been observable as a large jump from previous as GPS time to UTC should be stable. Maybe the condition could have been detected this way? Of coarse its hard to know when to not trust the control segment..What do you thin? Is there any possible fruit for this direction? Another idea for receivers to protect against this jump?

Thanks, Paul