No audio available for this content.

Position, navigation and timing (PNT) services, derived primarily from GNSS constellations, have become a critical element underpinning the global economy, with a vast range of sectors depending on these signals.

This includes coordinating financial transactions, stabilizing power grids as well as navigation, with supply chains set to become more reliant on the technology as autonomous vehicles become prevalent. However, GNSS is a vulnerable technology, with faint signals from medium-Earth orbit (MEO) satellites being susceptible to disruption.

In this article we’ll look at how both static and dynamic applications can achieve resilient PNT, with strategies and sensor fusion techniques that allow operational capability when GNSS is denied.

Seven hundred. That’s the number of GPS interference events such as jamming and spoofing that take place every single day, according to the U.S. government. And this number is increasing across North America and Western Europe, with it being especially prevalent in or near war zones.

Indeed, in August, the navigation system of a plane carrying the EU President, Ursula von de Leyen, was reportedly targeted by a GPS jamming attack as it was due to land in Bulgaria — forcing pilots to rely on paper maps. And GPS interference has been linked to the crash of Azerbaijan Airlines flight J2-8243, which was shot down on Christmas Day, 2024.

Relying on a single source for PNT is no longer a viable strategy and developing a resilient PNT ecosystem that can function in D3SOE (denied, degraded, and disrupted space operational environments) has become essential.

While navigation is the most commonly understood application of PNT, the timing component is critical in so many of the static systems we rely on — not just finance and power (as listed above) but for AI data centers, asset tracking systems and communication networks — which require precise and stable time references to ensure data integrity, and need these to be synchronized across global networks.

For such systems, the consequences of getting timing off by even the smallest amount can be seen in the 2016 decommissioning of the SVN23 GPS satellite. During this, a software error created a 13.7 microsecond anomaly across the entire constellation that, according to a UK government report caused issues with digital radio broadcasts and communication networks. The event is also seen by some as a warning for the financial sector and in particular for high-frequency trading (HFT), where trades take place in millionths and studies have suggested that a 1 ms advantage in trading applications could be worth $100 million a year to a major brokerage firm.

By subtly altering timing signals used by trading systems, malicious actors can effectively see and use market data “from the future” and enact transfers worth billions of dollars.

Similarly, a timing attack on the phasor measurement units (PMUs) used to measure real-time stress in power grids could trigger major blackouts. The effect of such an attack can be seen in 2003’s (pre-PMU) Northeast Blackout, in which a sagging power line touched tree and caused a series of cascading outages that affected 55 million people across the U.S. and Canada.

And further putting the importance of protecting PNT in context, in 2020 the U.S. defined 16 critical infrastructure sectors as part of its Executive Order 13905. Of these 14 (88%) of these are reliant on PNT for their safe operation. Going beyond the energy and finance examples above, this includes sectors like communications, transportation, and agriculture. In short, PNT resilience is essential across virtually the entire economy.

Detecting a Compromised GNSS Signal

Of course, the first stage in protecting a PNT signal is in the identification of an attack, and several techniques can be used to identify inconsistencies that point to jamming or spoofing.

These range from the analysis of the signal’s Doppler shift (transmissions from nearby terrestrial spoofer will have a near-zero Doppler shift) to techniques like RAIM (receiver autonomous integrity monitoring), which continually recalculates position while excluding one satellite each time to see if the results are consistent.

Cryptographic methods, such as Galileo’s Open Service Navigation Message Authentication (OSNMA), are also available to verify a satellite’s digital signature and confirm the data’s authenticity.

However, relying on cryptographic authentication alone still comes with risks. Notably, authenticated signals are susceptible to meaconing attacks, where a legitimate signal is recorded and replayed later to mislead a receiver. It is, however, possible to counter these attacks using a secure, out-of-band verification layer for all GNSS constellations. This involves the independent delivery of authentication data with hash authentication transmitted via encrypted L-band correction signals from geostationary (GEO) satellites.

This approach can also be retrofitted to older equipment using PNT by using an RSR transcoding device (see below).

For dynamic systems, an additional level of validation can be gained by inertial sensors, comparing their output against PNT data to detect both sudden large jumps in position and continual slight deviations that can be characteristic of a sophisticated spoofing attack.

Timing in Static Applications

The timing architecture of such systems must go beyond simply identifying a threat and validate incoming data. This requires the integration of alternative PNT sources through an intelligent sensor fusion framework. To achieve this level of resilience in a fixed location, a multi-source, zero-trust approach is necessary. This involves augmenting or replacing GNSS with a layered defense of terrestrial and alternative space-based signals that can be authenticated and trusted.

Modern PTP grandmasters utilize the latest sub-microsecond accuracy Precision Time Protocol (PTP) and the more common millisecond-range Network Time Protocol (NTP) to ensure compatibility with nearly all standard IT equipment.

High-speed 25G PTP Ethernet connections are also being implemented to support high-performance AI data centers and financial exchanges without creating data bottlenecks. To ensure continuous operation during extended GNSS outages, these systems can draw synchronization from terrestrial sources like a network PTP feed or an optional atomic caesium clock.

Furthermore, it is also possible to use encrypted L-Band signals from geostationary (GEO) satellites, such as those from Inmarsat, which create an enhanced timing service with built-in GNSS authentication and anti-spoofing features to deliver timing accuracy of sub-5 ns.

Navigation Without a North Star

While static applications can utilize fixed terrestrial infrastructure for backup, dynamic systems do not have this luxury.

The inherent weakness of RF signals makes them easy to overpower through deliberate jamming by hostile actors. As such, navigation systems onboard UAVs and autonomous vehicles, as well as manned commercial and military vehicles require self-contained navigation capabilities that can function reliably when GNSS signals are compromised. This has driven significant advances in inertial navigation.

Sensors like accelerometers and gyroscopes have become a critical source for orientation and direction data that remains available at all times. The development of micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) has been crucial, enabling the integration of inertial navigation into even the smallest systems.

These sensors aren’t an alternative to PNT satellites. By their very nature they will accumulate errors over time, with sensor bias causing drift and random-walk deviations allowing random noise in each measurement to accumulate. However, recent years have seen significant gains in their accuracy, allowing navigation to continue for short periods after GNSS data is compromised.

Combining these inertial sensors with sensor fusion techniques also allows each element in a multi sensor system (using magnetometer; and accelerometers/ gyroscopes for roll, pitch and yaw…) to be continually verified by the others for further improvements in accuracy, reducing overall level of error. Data from these IMUs can also be fused with signals from alternative satellite constellations like those in LEO.

LEO satellite signals are less accurate for timing than GNSS (around 80 ns vs. sub-15 ns) but are significantly stronger. For example, the Iridium LEO STL signal is c.1,000 times stronger than GNSS, making these signals both more resistant to jamming and harder to undertake a (successful) denial of service.

More recently, techniques using downward-facing camera to track fixed identifiable landmarks have been developed as an alternative / additional data validation method for dynamic systems.

These external sources provide absolute reference points that can be used to correct the inertial system’s calculations, dramatically improving accuracy and enabling reliable navigation for much longer periods.

Sensor Fusion Gives Resilience

The limitations of individual PNT sources — whether the vulnerability of GNSS or the inherent drift of inertial sensors — mean they cannot depend on a single technology. The most effective strategy is often a hybrid one, combining a high-accuracy inertial sensor unit with inputs from other sensors.

As we touched on above, adding data sources improves the ability to detect and counter PNT attacks. For example, the EU has confirmed it will deploy additional LEO satellites to bolster its ability to detect GPS interference. And vision cameras can also be used as part of a Visual-Aided Inertial Navigation System (VINS), which provides a powerful method for maintaining an accurate position in the complete absence of GNSS signals.

This technique was developed in 2025 by VIAVI’s Inertial Labs division, with VINS combining processing with multiple inertial sensors to maintain position. This is reinforced with, and calibrated by a 3D vision-based positioning algorithm that compares visual patterns captured by an onboard camera (either daylight or infrared) with pre-loaded, satellite-imagery-derived 3D maps to track against known landmarks. In a GNSS-denied environment, a VINS system can maintain a horizontal position within 35 m, a vertical position within 5 m, and a desired velocity within 0.9 m/s.

Conclusion: Bridging the Legacy Gap

While modern systems can be designed from the ground up with a multi-layered, sensor-fusion PNT architecture, there is still the problem of the huge number of legacy systems that are very much prone to attack.

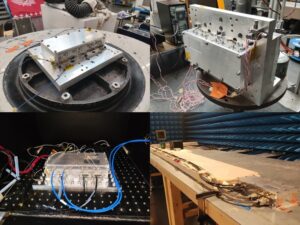

These legacy PNT systems are still widely used, including in military conflicts where D3SOE attacks are prevalent. To address this vulnerability, resilient signal retransmission technology has been developed to cost-effectively upgrade these older systems. This approach uses RSR transcoders (constellation simulators) to take a trusted PNT signal, derived from multiple assured inputs, and convert it into the standard GPS format that legacy equipment is designed to receive. This set up – in which the GNSS aerial is replaced with the input from the RSR transcoder – allows the existing systems to operate with state-of-the-art resilience without requiring replacement.

But, as we’ve seen in the above, a single, invulnerable replacement for GPS is simply not possible, so integrating multiple trusted sources is therefore essential. The path to assured PNT relies on a multi-layered ecosystem of diverse signals and sensors and applying this approach to both modern designs and legacy-system upgrades ensures all assets can maintain uninterrupted PNT access.