No audio available for this content.

The 2025 Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) Workshop in Jakarta, Indonesia, emphasized one important message: navigation satellite data has become a fundamental necessity in modern life, yet Indonesia remains completely dependent on systems owned by other countries.

The workshop was held by the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) in collaboration with the University of Indonesia (UI) and the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA), at the BJ Habibie BRIN Building, Nov. 17–21.

“Indonesia cannot just be a market. In the future, we must also become a producer of satellite services and have our own satellite industry.”

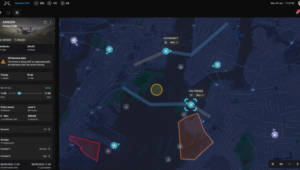

Navigation satellites are a “silent technology” whose contribution is rarely recognized, yet they support almost all location- and time-based activities, explained Rr. Erna Sri Adiningsih, director of the Secretariat of the Indonesian Space Agency (INASA). “When we use Google Maps, search for addresses, find directions or positions, everything relies on data from navigation satellites,” she said. Even robotics, drones, aviation systems, and global time synchronization operate thanks to satellite navigation services.

Therefore, she emphasized that disruptions to the navigation system would have direct implications for public activities. “If a navigation satellite operator stops operating or malfunctions, most of our communication devices will cease to function. Time won’t synchronize, location won’t be read, and robotics and drones won’t operate,” she said.

Adiningsih added that the workshop is crucial for connecting operators with users. “We want to ensure that the needs of users from various countries are understood,” she said.

The 2025 GNSS Workshop is a strategic platform for bringing together the GNSS operator community with national stakeholders such as the Ministry of Transportation, AirNav Indonesia, academia and the industrial sector. BRIN itself operates the experimental A1, A2 and A3 satellites, but does not yet have a navigation satellite.

Crucial time for increased capacity

Indonesia, Adiningsih said, is at a crucial point in increasing its capacity. Despite having the capability to build micro-satellites for earth monitoring and privately operated communications satellites, navigation satellite technology requires mastery of a different system. “Indonesia has never built a navigation satellite. We are still in the stage of utilizing the data, not building the satellites,” she said.

Augmentation. The development of navigation augmentation systems for aviation, drones and maritime transportation currently relies on ground-based equipment managed by the Geospatial Information Agency (BIG). These are expensive and have limited coverage. “If we use a satellite system, one system can be used across the entire region without having to install ground-based equipment,” Adiningsih said.

Therefore, Indonesia requires integrated policies and support from various ministries and agencies. The national space program already has a clear direction through Space Policy 2045, including a target for technological independence. “Indonesia cannot just be a market. In the future, we must also become a producer of satellite services and have our own satellite industry,” she emphasized.

Adiningsih hopes that the five-day workshop will not only serve as a forum for sharing experiences but also open up opportunities for international collaboration in the development of satellite navigation technology and systems. “With humanity’s increasing dependence on satellite data, Indonesia must begin building its capabilities so that it is not completely dependent on other countries,” she said.